Transfiguration in the Clouds

Homily delivered by the Rev. Rhonda J. Rubinson

Church of the Intercession, NYC

August 6, 2017

Text: Luke 9:28-36

In the name of God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Amen.

Today is Transfiguration Sunday, when we celebrate the vision that Jesus gives Peter, James, and John at the top of a mountain. That is a very important day in church history; it has been celebrated for two millennia in many ways, including in church names – there are many Churches of the Transfiguration. We have one in Manhattan: ours is on 29th Street and 5th Avenue, also known as “the Little Church Around the Corner.”

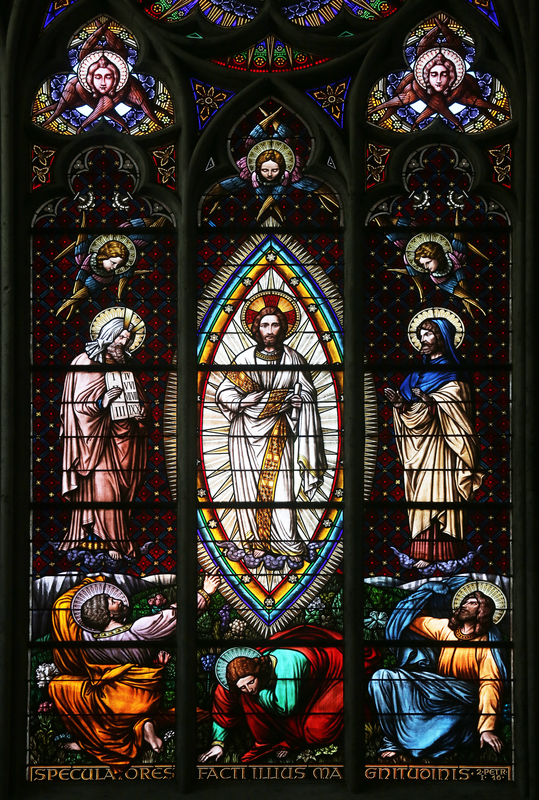

Also there is much art devoted to depicting the Transfiguration. There is a wonderful stained glass “Transfiguration Window” directly above the altar in Saint Saviour’s Chapel at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. And throughout the ages it’s been a particularly fun challenge for artists to capture the dazzling light emanating from Jesus and striking down Peter, James, and John in awe. The most famous painting among many is perhaps Raphael’s Transfiguration, which was his last painting before his death. One almost senses that he was anticipating what he would see when he crossed over to heaven as he painted.

But in addition to being a very important day for the church, today is also a very important day in our national and our world’s history. August 6, 1945 was the first time ever that an atomic bomb was dropped in war. We, the United States, dropped two atomic bombs on Japan: the first on August 6, 1945 on Hiroshima, and the second three days, August 9, on Nagasaki. These were the only times in history – so far – that nuclear weapons have ever been used in war.

It must have been on the 50th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, which was also a Transfiguration Sunday, that I heard an unforgettable sermon at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine by James Carroll, the former Roman Catholic priest, author, peace activist, and very vocal critic of the Roman Catholic church – all of which credentials is why the Cathedral’s Dean James Parks Morton often invited him to preach. I remember one of the main points of his sermon that day, which I’d like to share with you today.

Carroll spoke about how hard it is sometimes to tell the difference between someone who is being born and someone who is dying. I remember him saying that if we watch a woman give birth, there is pain, there is blood, there is quite often screaming, sometimes there is the death of the mother; it is very alarming and the sense of danger is palpable (in fact, childbirth historically has been very dangerous to the mother’s life). The result of all this suffering, though, is new life. This is how every one of us came into the world: through trauma.

Carroll then spoke about Hiroshima, and about how there was pain, suffering, blood, and death – and it was horrific, but if we are Christians, we know that this was also prelude to new life, the next life, for those who suffered and died on that terrible day. The reason we can say this is because if we are Christians, we profess to believe in Jesus who was crucified: and there was pain, blood, suffering and death, which was also prelude to the new life of the resurrection.

Now of course I am not in any way justifying causing suffering or horror or terrorism or murder, nor am I taking a side in the debate over whether dropping the atomic bombs in Japan was justified. What I am attempting to do is take a long-view perspective on what God always ultimately makes out of suffering and death: that is life.

With our limited human perspective we have trouble taking in the long view, seeing the whole picture. That’s part of the message of the Transfiguration today. The disciples, especially the ones closest to Jesus – Peter, James, and John – spent a great deal of time with Jesus. They heard him teach, shared many meals with him; they even traveled together – and I’m sure you’ve all heard the old saying that you don’t really know someone until you travel with them. (It’s true. I’ve had some friendships nearly end after some terrible trips with close friends).

Despite all of the quality time they’ve spent with Jesus, the disciples really don’t know who he is. Jesus must have looked fairly ordinary – a typical Jew of his time and place – this was his human side of course. But the disciples were just like us, and could only see part of the picture; even though they knew Jesus, followed him, respected him, even to a degree worshipped him while he was alive, they did not have a true sense of his divinity.

Odd as this may sound, the vision in the Transfiguration is not only about Jesus – it’s about this thing we’re talking about, this inability for humanity to have a clear vision about God’s long view, the constant creation of life out of death because of God’s endless, unfathomable love for us. We just heard what the vision of the Transfiguration looked like – dazzling light pouring from Jesus, but the Transfiguration is not only or even mainly about light, it is also about darkness. A big part of the message is that true faith is found in darkness, even when the light is completely swallowed up by clouds.

This is a consistent theme throughout the Bible – God seems to regularly use clouds as a test of trust and faith. Remember that the Hebrews going through the desert were led by two pillars during the Exodus: a pillar of fire, which lit their way forward at night, and a pillar of cloud, which protected the Israelites during the day but which was also the sign that the nation was to put up camp, sit still, and wait. They could only move again when the pillar of cloud lifted. In the meantime, while sitting under the cloud, they had to trust in what they couldn’t see, that God was still there, that a path to the Promised Land was still there, even when both were invisible.

A similar phenomenon is in today’s gospel. After his conversation with Moses and Elijah, Jesus lights up – and Peter, James, and John must have been thinking, “Wow, we can follow that!” But then see what happens just a few seconds later: the gospel says that a “cloud came and overshadowed them, and they were terrified as they entered the cloud.” All of a sudden they were in a blackout, they could not see a thing. They immediately lost their nerve and their faith, and fell headlong into fear, just moments after witnessing the most amazing vision of their lives.

It is within this dark cloud – notice, not in the light – that God’s voice is heard: “This is my Son, my chosen. Listen to him.” In other words, God is saying that even if you can’t make anything out in the darkness around you, trust Jesus.

Church, we are living in dark and darkening times; we can sense the clouds closing in around us. I know that in my own lifetime I’ve seen some very dark times in our country and in our world – the assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy and the Martin Luther King, Jr.; the Viet Nam war and the protests surrounding it which ripped our country apart; Watergate and the resignation of Pres. Nixon; the horror of September 11 and the awful misguided and destructive war in Iraq which followed; Hurricane Katrina, Superstorm Sandy and much, much more.

Yet through all of those, the clouds of darkness and uncertainty never felt quite like they do now. Through all that went before, it always felt like we could rely on certain bedrock principals in our society and in our government: even if they were being challenged or disrespected, at least they were there. Now it feels like that bedrock foundation is crumbling to dust.

But the lesson of the Transfiguration is that even in the deepest darkest clouds, God is still there, Jesus is still there. The difference between Christianity and every other world religion is that Jesus promises to be with us no matter what. Even if we cannot see the dazzle of Jesus’ robes, even if we don’t know what lies on the path ahead of us or even where the path is, he is asking us to trust that he is still there, to trust in him.

Sometimes we forget that this is why we come to church; we forget what church is really about. We can become distracted by our rituals, even our fellowship. The real reason we come to church is to remind ourselves that nothing in this world is deeper, surer, sweeter,or more comforting than the knowledge that no matter what happens around us, Jesus is still our foundation. Everything around us can abandon us, fail, die, or leave and Jesus will still be there. This is not an empty creed, mere words devoid of meaning. And we need to remember it now more than ever.

I’d like to close with a prayer adapted from the Book of Common Prayer.

Let us pray.

Almighty God, save us from violence, discord, and confusion; from pride and arrogance, and from every evil way. Defend our liberties, and fashion into one united people the multitudes brought here out of many nations and tongues. Give the spirit of wisdom to those in whom we entrust the authority of government, that there may be justice and peace at home, and that, through obedience to you law, and trust in your presence, we may show forth your love and light among the nations of the earth, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

0 Comments